|

By

Charles M. LucasJ

The Arlington

Advocate, Thursday, April 2, 1981 p.29

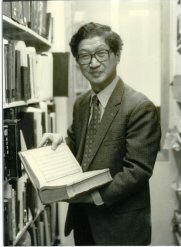

For 30 years John

Yung-hsiang Lai has helped scholars research information. He beams

when Harvard graduate students come to the Yenching Library on

Divinity st.,Cambridge, knowing that Associate Librarian Lai will

show them sources in their quest to write “A” theses.

The nine-year

Arlington resident says, “A library is a treasure of information. It

contains records of everything that has ever happened. The librarian

lets the public use the treasure. And I enjoy giving assistance to

those wanting to acquire knowledge.”

Lai’s bibliophile

career began in 1951 at National Taiwan University. [He worked at

the Library and] taught library science there for more than two

decades. Harvard University, aware of his background and that he

understood Chinese, Japanese and English, invited him to the Yenching Library in 1972.

Yenching Library,

the largest East Asian University library outside Asia, contains

600,000 books on five floors. The languages of the volumes vary from

Chinese, Japanese and Korean to Manchu, Mongolian and Vietnamese.

In a glass case

by the entrance’s swinging doors, the library is exhibiting its

Chinese language missionary work collection. A geographical history

of the United States by the first american missionary to china,

Reverend Bridgeman, faces the viewer from the third shelf.

Pages from the

first Chinese tract, “The Sermon 0n the Mount,” printed in 1834,

reflect on the glass plate above Bridgeman’s compilation. The

collection also includes

Christian primers

formed in the Chinese three-character model and the original first

Chinese translation (1813) of the New Testament.

Lai says,

‘European missionaries were the first ones who westernized China.

They were ambassadors who introduced European civilization to the

Orient. Prior to the Opium War (1842), the Chinese government

prohibited the distribution of Christian literature. Men like

Reverend Morrison of the London Missionary Society, had to publish

translated clergical tracts underground.”

After the opening

of the ports (1865), missionaries intrduced Taiwan to the Anglo

culture. They taught Western traditions and made onverts in Lai’s

native country, where five percent of the Taiwanese practice

Christianity today. However, since the Communist takeover of China

in 1949, all western influence has diminished on the mainland.

Lai adds,

“Besides religious tracts, the missionaries also translated volumes

of Western works in international law, ethics and psychology,etc.

The missionaries gave an overall perspctive of their countries--not

just a religious one.”

The American

Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions donated a collection of

Protestant missionary works in te Orient to the Harvard-Yenching

Library at the same time of the Communist takeover of China. Lai

compiled a catalog of those 1000 original books, which G.K.Hall and

Co.ublished last summer. Lai’s text attracts readers to Yenching

because it indexes the largest assortment of oriental works in the

romanized style (26 characters), rather than the chinese style which

has 50,000 characters.

In addition to

writing other library research guides, such as “The New

Classification Scheme for Chinese Libraries,” Lai’s inquiries into

Taiwan’s past inspired him to compose “Studies of History of

Taiwan.” He leans both elbows on his office desk and elaborates on

his classification book. “It shows how to organize library

collections. The system that it describes is widely used in

libraries throughout Taiwan, Hong Kong and Malaysia.”

Lai studied

library science at George Peabody College for Teachers in Tennessee

on his first trek to the United States in the late 1950’s. National

University of Taiwan’s Library Science Department promoted him to

head upon his return home.

Twice during the

1960s he traveled across the Pacific Ocean to resent papers at the

American-hosted International Congress of Orientalists and the

Library Educational Congress for Developing Countries.

Lai accepted

Harvard’s invitation to work at Yenching because he wanted to keep

his family together. He explains, “My daughter and two sons planned

to live in the States. My wife,Helen, and I didn’t want to stay so

far away from tem, so I took Harvard’s offer. Chen-li Lee, my

daughter, has followed in my footsteps.” Lai, his smile broadening,

declares, “She works at Wilmington’s Avco Systems Library.”

Residing in

Cambridge for a year, he moved to Arlington in 1973. Although

baptized a Presbyterian in Taiwan, Lai attends Arlington’s Calvary

Methodist Church services, explaining, “No Presbyterian churches are

close to my house. And considering that Methodists don’t differ much

from presbyterians in concept, I started goin to Calvary Methodist.”

He obtaied his

American citizen status four years ago. In the meantime he visited

Taiwan once for his mother’s funeral. He may go back again, but has

made no specific plans.

Last year’s

president of the Chinese-American Librarians Association and a

current member of the American Library Association, he reflects..The

United States is my home and the home of my children. Harvard’s

Yenching Library has few peers in size and none in information

accessibility and cnvenience. Harvard University’s Library, taken as

a hole, has the greatest treasures in the world. In what other place

would i want to be?”

The Yenching

Library, which was established in 1928, is open Monday through

Saturday from 9 a.m.to 10 p.m. One of the oldest books in the

library,which carries volumes on many subjects, is a 960 A.D.book

from the Sung Dynasty in China.

|